AQ.0013

Toshiko Takaezu:

Diptych of Closed Forms

2 Select Acquisitions

•

Acquired Mar 2023

Pairing of Closed Forms

Untitled, ca. 1990s, Glazed porcelain, 16 1/2 x 8 1/2 x 8 1/2 in. (41.9 x 21.6 x 21.6 cm)

Closed Form (with rattle), n.d., Glazed stoneware, 6 x 4 x 4 in (15.2 x 10.2 x 10.2 cm)

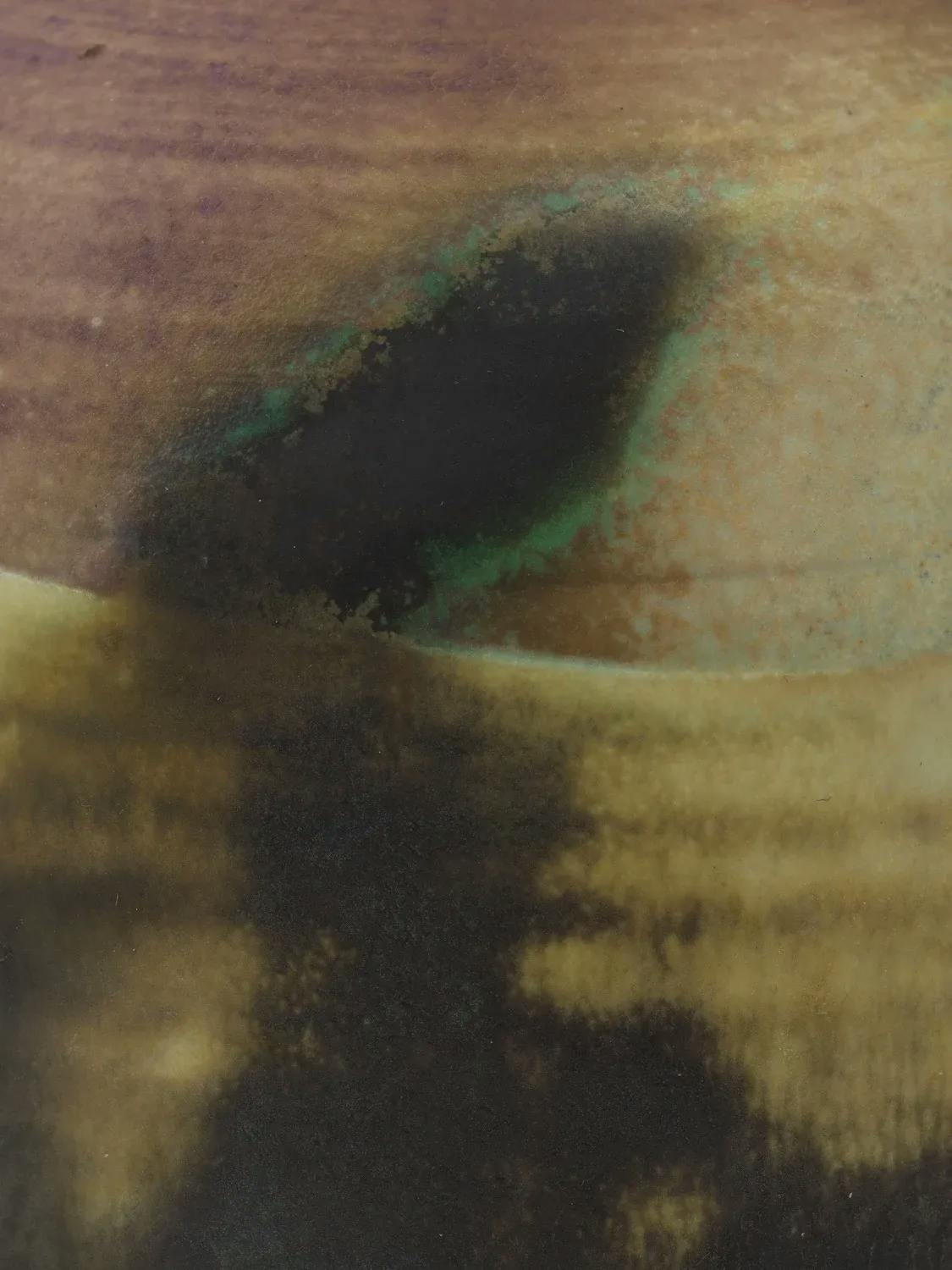

Takaezu often worked and exhibited in series–placing her works in dialogue with one another. This pairing was not conceived in the artist’s studio but by Arkive’s curatorial team as a way to distill two great examples of Takaezu’s work that speak to different ways of working. The taller of the pots, the white, is made of porcelain, the finest typology of ceramic (the alternatives being stoneware and earthenware). The lunar cream color is typical to porcelain and in this case is decorated with misty patches of black and blue. These moments of color evoke the bedewed haze of Hawaii and the scorched fields of lava after the eruption. They also have been compared to Japanese scroll paintings where inky washes stand in for land and sea and sky. Applied like an action painter might and then manipulated and singed in the fiery will of the kiln, the resulting work calls to mind the splashes and strokes by her Abstract Expressionist contemporaries Franz Kline and Helen Frankenthaler. These kinds of painterly brushstrokes are shared with the smaller vessel, which appears to have been dipped directly in glaze as well.

As far as silhouette goes, both sculptures share the pronounced navel that was the exterior signature of Takaezu’s closed forms. Both works bear evidence of the pottery wheel but on the taller one the ribbing running up the side is less pronounced, lost in the hazy glaze. The taller of the vases also seems to have a waist and therefore a more bodily appearance. The shorter one is sized to be held in the hands–a perfectly tactile example of her poetic series of rattles.

In the 1960s just as Toshiko Takaezu was beginning to create her closed forms, the artist began using them to “send messages”. She took slips of paper and balled wordless poems around a piece of wet clay that she would then drop into a vessel before sealing it up. In the kiln, the paper would burn away and the nugget would harden, turning the work into a makeshift bell that is imperceptible in a photograph but adds new dimension and intimacy to the in-person viewing experience. As one writer observed: “the sound from a Takaezu pot affirms the existence of the interior.”

Like all the serendipitous evolutions of Takaezu’s work, the first rattle was an accident according to an interview with the artist. She was trimming the top of a pot and a piece fell in. She is also said to have written poems on the inside of some works, but only breakage would reveal them to the world.

Overview

Meet Toshiko Takaezu

Takaezu paddling the top of a hand-built form. Photo Credit: Ben Eberle, 2003. Courtesy of The Family of Toshiko Takaezu.

Toshiko Takaezu is one of the twentieth century’s most influential abstract artists. Born in Pepeekeo, Hawaii in 1922 to Japanese emigre parents, Takaezu studied ceramics first with Claude Horan, the founder of the ceramics program at the University of Hawaii, and later with the influential Finnish-American ceramicist Maija Grotell at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan. Already in this early phase in her career, Takaezu was able to see correspondences between Abstract Expressionism and the spiritually infused traditions of East Asia, such as calligraphy and tea ceremony. Gifted with prodigious drive and vision, she combined these diverse inspirations arriving at a powerful synthesis. Takaezu was instrumental in the post-war reconceptualization of ceramics from the functional craft tradition to the realm of fine art.

Takaezu was a devoted maker and educator, teaching first at the Cleveland Institute of Art and then at Princeton University, until her retirement in 1992. She lived and worked on a lush property in rural New Jersey, establishing a steady studio practice and firing her work on site with the aid of apprentices. Takaezu passed away in Honolulu on March 9, 2011.

Throughout the artist’s lifetime, her work was exhibited widely in the United States and Japan, including a solo exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (2004) and a retrospective at the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto, Japan (1995). Her work is represented in collections including the Art Institute of Chicago, DeYoung/Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, Honolulu Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Recent exhibitions include the 2022 edition of the Venice Biennale, The Milk of Dreams curated by Cecilia Alemani. In February 2024, The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum will host the first touring retrospective of Takaezu’s work in twenty years. The exhibition will be accompanied by a new monograph and will travel to the Cranbrook Art Museum (2024–25), the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (2025), and the Honolulu Museum of Art (2026). A complementary large-scale installation will open at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in October 2023.

Artist

Ghosts in the Kiln

Does art have a function? Does craft need one? And where do these expressions meet one another? The late artist Toshiko Takaezu didn’t set out to turn these concerns inside out but she did it all the same. As the leading figure of America’s first wave of genre-demolishing ceramicists who emerged with World Wars and the Industrial Revolution in their rear view mirror, Takaezu sought to capture the modern condition in all its complexities and contradictions. For her painterly counterparts, the action-driven Abstract Expressionists, this meant diving deeper into authorship than anyone had before, focusing on how individual actions—even quick flicks of the wrist—could be immortalized in paint and reflect the whole. But for Takaezu, the autobiography was nowhere in sight. Rather than trying to heroicize human accomplishment or even her own expertise as a master ceramicist, her focus instead was on trying to make permanent houses for what we will never know–fragile vessels whose darkened interiors, often made invisible, were as important as their hand-decorated faces.

In 1958, Takaezu created her first closed form. Evolving out of her early biomorphic multi-spouted vases and teapots, these new works with no discernable opening abandoned the functionality of their predecessors to make room for wonder. With only sometimes a navel to speak of, the outside of Takaezu’s clay forms became a continuous, three-dimensional canvas that the artist could decorate to point the viewer inwards. The artist’s bold palette of cobalt blue, greens, yellows and reds reflect the kaleidoscope of her childhood home: Hawaii. To conjure the elemental, Takaezu leaned towards techniques that she shared with her Abstract Expressionist peers—huge swipes, chance dribs and drabs, and sometimes even fingerprints. But the overall effect of these gestures was less about historicizing her hand than about striking up a conversation with gravity and the kiln. What is a kiln other than a chance machine where spontaneous chemical combustions can throw intention into unexpected spirals?

Creating space for the unseen is a task Takaezu continued to attend to throughout her five decade long career with monkish devotion. She got up in the mornings at her studio in New Jersey, did yoga, tended her garden, went to the studio, cleaned it, cooked dinner and began again. She never dated her work consciously or kept track of it because she never drew distinctions between her tasks and the objects they produced. Takaezu was a lifelong teacher and student, for whom works only took on meaning afterwards, but in the moment of conception were vehicles to not only get closer to the divine but also to the everyday.

On March 6, 2023, Arkive launched an acquisition round titled “Ghost in the Kiln,” engaging in dialogue, discussion, and debate on the work of Toshiko Takaezu. Closed Form (with rattle), n.d and Untitled, ca. 1990s were considered alongside Untitled, 1980s-90s and Untitled, ca. 1990s.

After a series of votes, the community selected Closed Form (with rattle), n.d and Untitled, ca. 1990s as the seventeenth and eighteenth acquisitions into the collection. Core team members then worked with the New York City-based James Cohan Gallery to acquire the work. Closed Form (with rattle), n.d and Untitled, ca. 1990s will go on display via long-term residency at a prominent public location, as selected by the Arkive membership.

About the acquisition

Select Member Comments

Conversation

Additional Materials

We encourage you to read further into Toshiko Takaezu, her works, and her career. To kickstart the process, please find a few selected readings and interviews below. As always, this is just the start. Apply to Arkive to continue the conversation with the community.

- Foundation website

- New York Times

- Artforum

- An Interview with Toshiko Takaezu, D.B Long Film, 2009

- Toshiko Takaezu: In the Stars, NJ State of the Arts, 2006