Myth Maker

Lynn Hershmann Leeson’s black-and-white photo collage series, “Phantom Limb” (1985-87), features female bodies merged with machines—cameras, clocks, electric plugs, binoculars, etc. When I first saw them, I thought of the Dada artist Hannah Hoch, whose pioneering photomontages similarly explored the thorny intersections of mass media, technology, and gender. Hoch’s 1920 work Beautiful Girl, for example, takes a magazine image of the era’s iconic New Woman, dressed fashionably in a bathing suit with a parasol in hand, and gives her a giant light bulb for a head. Her other hand is notably amputated. Surrounded by bicycle wheels, BMW logos, a pocket watch, and other mechanical symbols of capitalist progress, this cyborgian New Woman became both the object and consumer of her own myth.

Leeson’s “Phantom Limb” series similarly reflects the ways in which, as women, our self-perceptions are shaped by mass media’s inevitable pull. Yet the solitary, model-like women in her photographs, who are so seamlessly integrated with their machinery, suggest a naturalized intimacy between the body and machine that can no longer be disentangled. Instead, the artist writes in her 2014 essay “The Terror of Immortality” that, “the implicit strategy of these robotic female cyborgs is that they are posed and poised to outwit their captors. They are complicit in the action and understand fully what is being done to them, and therefore they seek to avenge themselves by reversing, revising, and transforming the very dynamic of absorption and consumption, seduction and defiance.” By imbuing these hybrid sci-fi figures with such emancipatory potential, Leeson’s series anticipated the cyberfeminist art that emerged in the aftermath of the World Wide Web’s launch in 1991.

Leeson’s trailblazing forays into new media are now the stuff of legends, thanks in large part to her recent retrospective at the New Museum, “Twisted” (2021), which included hundreds of works made by the artist from the 1960s to the present. What most people don’t know is that this show represented only a tiny fraction of her output, or that her cyborg interests began with a happy accident in 1965. When the artist tried to xerox a drawing of a female figure, it got stuck, resulting in a rumpled, distorted body. The machine-assisted image appealed to Leeson, and she began creating more images of technically-assisted bodies like Colin (1969), a drawing of a man with a whirling rotor for a heart. Even her interactive “Breathing Machines” (1965-68) can be construed as cyborgian. This series of self-portraits, comprising sculpted wax faces covered in wigs and embedded with motion sensors, were installed on low pedestals in shadow-box style frames. Once triggered, these robotic chimeras would speak to viewers, asking questions, and emitting sounds of labored breathing. In her essay for the catalog accompanying the New Museum exhibition, writer Karen Archey describes the haunting works as existing in an “abject limbo between aliveness and lifelessness, somnolence and torpor.”

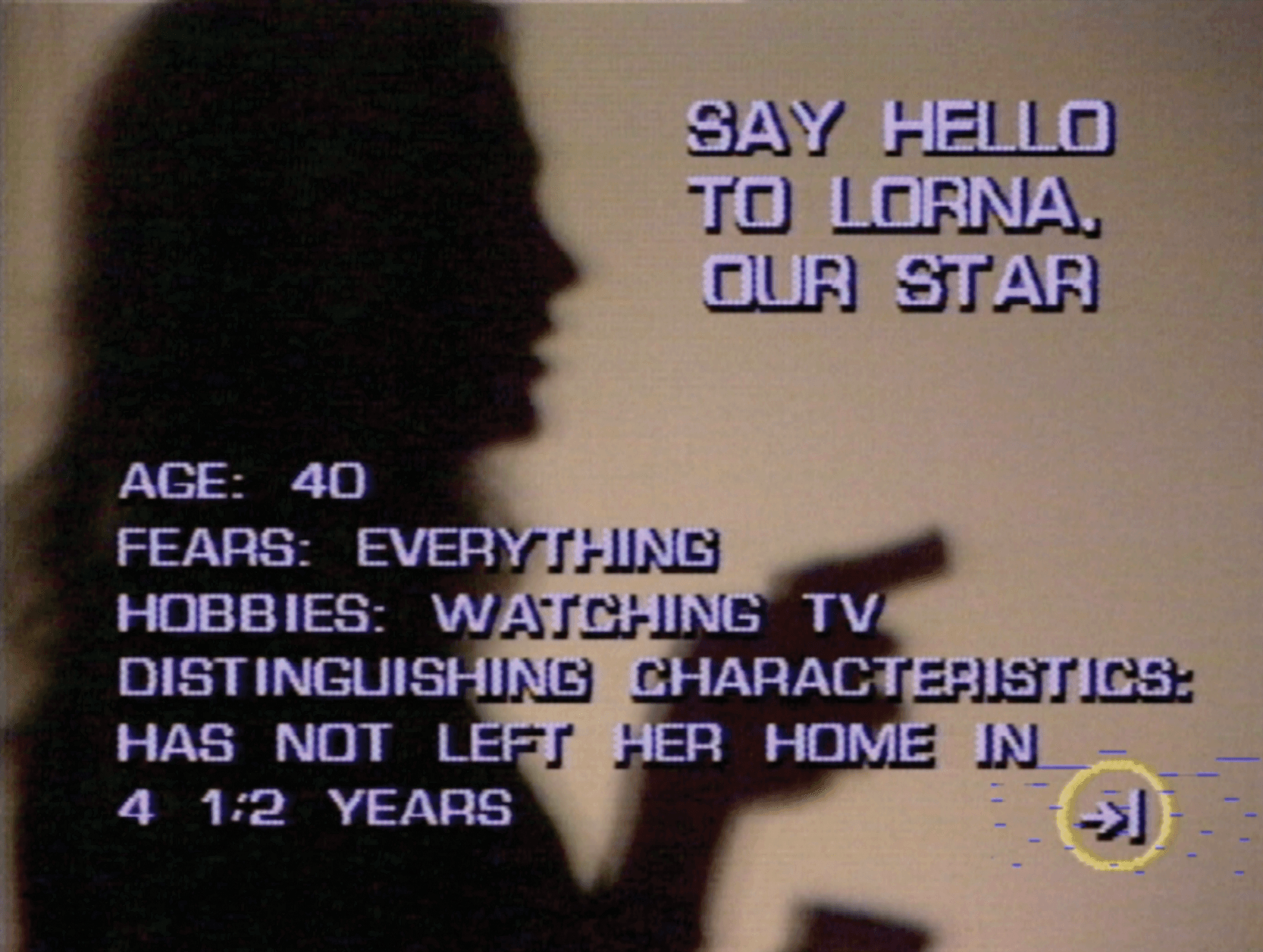

Still from Lorna, 1983, video

With Lorna (1983), the world’s first interactive work using laserdisc technology, the interactive aspects of the “Breathing Machines” became more pointed by underscoring the viewer’s complicity. And where the artist’s previous alter ego, Roberta Breitmore (1972-78), lived large in the world, getting her own driver’s license and attending EST and Weight Watchers meetings, Lorna was an agoraphobic who never left her tiny apartment. Instead, she waited there for us to meet her, poised on a pink wooden chair across from the television she watched day and night. This screen-within-a-screen scenario subversively defied video’s characteristic passivity by inviting audience participation. Using a remote control, viewers could learn about Lorna’s life and direct her action by selecting from a series of numbered icons placed throughout the room. In essence, Lorna’s fate lay in our hands. We could activate her to shoot her television, kill herself, or move to Los Angeles.

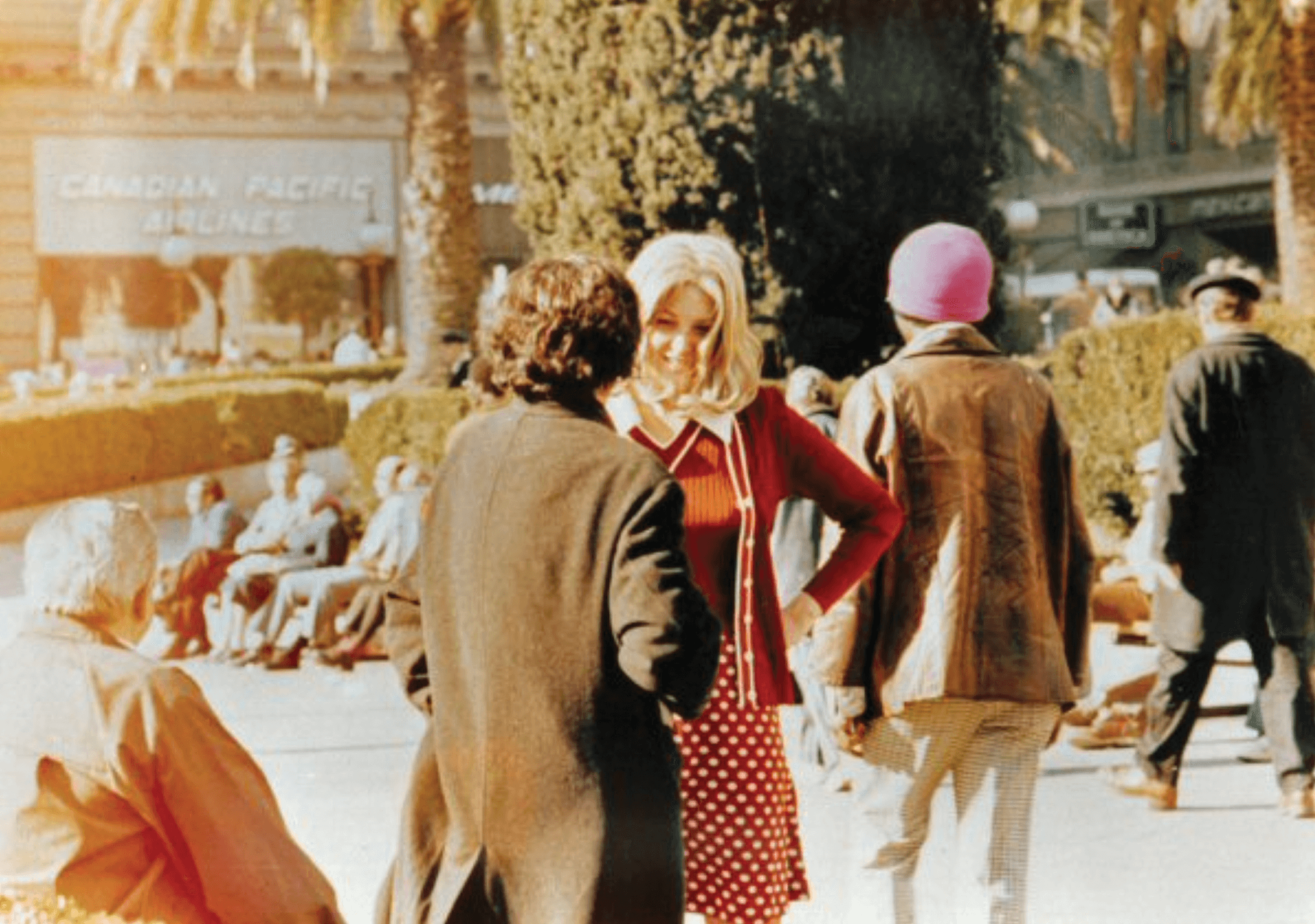

Roberta Breitmore, 1972-78, performance

1984 was also the year Leeson turned the camera on herself, embarking on a decades-long inquiry into the nature of self in a technological age that would see the advent of AI, bioengineering, and digital surveillance redefine the very notion of humanity. This work, Electronic Diaries, 1984-2019, is perhaps the artist’s most personal examination of such themes, and to sit through just the hour-long edit of this massive documentation is to enter a realm of revelations that even the artist’s therapist was not privy to. “A cyborgian future, that’s what I see,” she declares at one point, musing throughout on the omnipotent presence of technology in our lives, which she connects not only to her own stories of pain, struggle, and self-evolution, but those of friends and strangers on the news as well.

Made just as this deeply confessional project was getting underway, Seduction, 1985, is perhaps the quintessential representation of Leeson’s “Phantom Limb” series and its cyberfeminist leanings. It depicts a young femme fatale lying across a bed in a tight black dress, her come-hither pose, long legs, pointy-toed heels, and outstretched arms beckoning us closer. Inside the TV set that encases and replaces her head, a pair of enlarged eyes, closed in erotic contemplation, replete with Dali-esque eyelashes, fills the screen. I asked Leeson what the image means to her now, in a digital age of avatars and social media, and if its member-driven acquisition by Arkive changes any of that. This was her reply: “I feel the same as I did when I made it in the 1980s. We need to be aware of how technology tracks us and what it does to our identity. In the mid ’80s, it was with cameras; now it is with invisible surveillance strategies and algorithms. In both, individuals become the targets of corporate greed unless they are constantly vigilant.” We are what we watch. But what watches us, they also seem to ask, while perhaps dreaming of escape and revenge?