Moving Past Prometheus

The stage at Moscone is dark. It’s just past nine in the morning on January 9, 2007 when the thin man in the black turtleneck makes his way onto the stage.

“This is the day I’ve been looking forward to for two and a half years.”

Steve Jobs steps to the center. A thin grin spreads across his face.

“Every once in a while, a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything,” he says.

Enter the iPhone.

In the decade and a half since Jobs’s reveal, we’ve seen a version of this scene reenacted a thousand times by lesser Caesars.

The lone founder. The dark stage. The beam of light. The promise to change the world.

In our cultural lore, these founders are, to steal a Jobsism, the crazy ones.

They retreat from a society that doesn’t appreciate them. They go into the abyss and do battle with the Gods. They emerge with that spark of genius that lights a new era for human progress. It’s a trope that stretches back to Ancient Greece.

Prometheus, a Titan and ally of Zeus, betrays the Gods for the benefit of humanity. He steals fire and gives it to humans to incubate the arts and the sciences. Prometheus hopes that humans will worship him like a God. Instead, Zeus catches and punishes him. Zeus chains him to a mountain and, every day, an Eagle feasts on his freshly regrown immortal liver. The liver was, in Greek culture, a symbol of emotions. For the hubris of invention, an eagle steals Prometheus’s humanity from him each day.

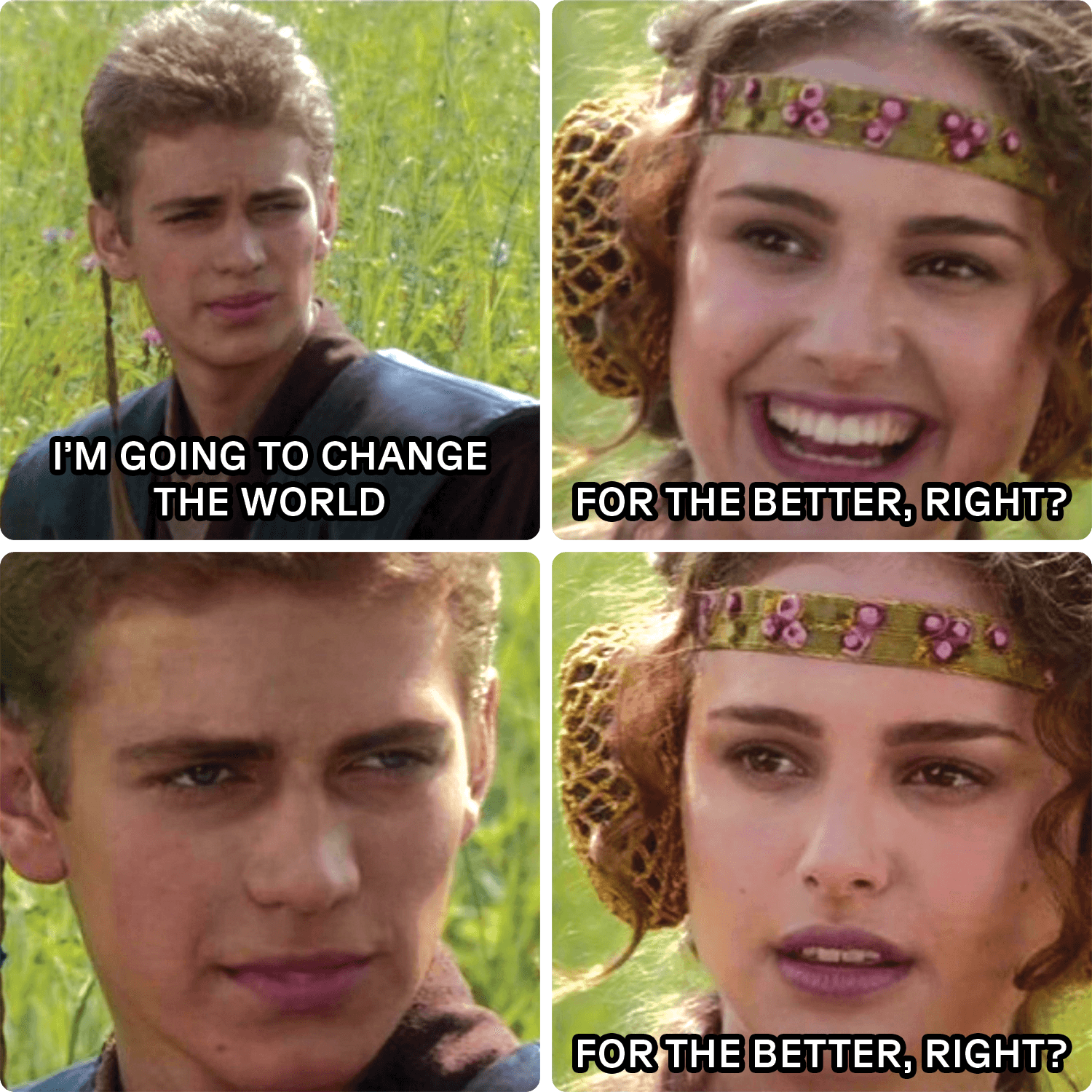

It’s a powerful story. It’s the myth that has launched a thousand startups. It vests an inventor with an incredible amount of agency. The hero alone is about to change the world in a way that even the Gods can’t undo.

But, if you pay attention, the story also exposes the problems with the lone founder hero. The inventor stands alone. He is the subject of the story. The world—and every other person in it—is a Non-player Character that he is here to disrupt. Will that change be for the better?

Mary Shelley wasn’t so sure. Her 1818 novel, Frankenstein, tells how a mad scientist conjures a monster. Its subtitle is “The Modern Prometheus.”

Today, we characterize anyone opposed to technological progress as a “Luddite.” But Mary Shelley came of age when the actual Luddites were revolting across England. They burned factory looms and protested technological progress for stealing craftsmen’s jobs. They seem to have influenced her. The author distrusted technology. She worried that the unquestioned, linear advance of technology was a Faustian bargain.

Our central technological debate uncritically accepts the same premises of Shelley’s England. There are Prometheans who worship progress and Luddites who yell “Stop.”

We hear echoes of this debate in discussions of Artificial General Intelligence. We hear them when we debate if innovation or degrowth is the way out of climate change. We hear them when regulators argue for shutting down social media or Web3.

Arkive’s “When Technology Was a Game Changer” collection asks us to turn the page on this dated debate entirely.

Technology, it argues, is not an alien force stolen from the Gods. It is not an external power that acts upon us. It is not just a “magical lever” that inexorably changes the world when pulled. We do not live, and never have, in a paradigm that is so simple or mechanistic.

Technology is not a unidirectional force. It is bidirectional. It shapes us as we shape it. We should reject the idea of the lone genius in favor of the broader view that creation is always a social act. It is a collaboration between creators. It is a conversation between builder and user. It is a response to the culture that surrounds it. We discuss, we create, we receive feedback, and we progress together.

But, to move forward with this new narrative, we have to reanalyze our past to extract new lessons. And that means recontextualizing our journey so far. Technology is not the hero of human progress, but an object of it forged in our collective conversation. It is not the lone, isolated genius, but instead those individuals who listen to the ever-expanding chorus that will guide us into the future.

Web 2.0 and the Voice of Data

In the beginning, there was the “ship date.”

A team of builders invested their energy to hit a launch milestone. They loaded up the boxes and shipped their product into the world. If they were lucky, their technology changed the world.

This, for sure, was a Promethean process. The builders conferred with the muses and tried to bring us back fire.

But the internet changed this process. The Big Build was replaced with the lean startup. Google, Facebook, and other Web2 darlings won by engaging in constant conversation with their audience. They shipped, learned, and iterated. Launching went from finish line to starting line.

This world of Prometheus gave way to the world of Mark Zuckerberg. Zuckerberg’s story features less obvious divine punishment. But it holds as many lessons for technologists.

In September 2006, Facebook launched the News Feed. Mark Zuckerberg realized that people logged on just to check friends’ profile updates. So, he thought to himself, “Why not put all the updates on the home page?” The News Feed was born.

Users hated it. Or at least that’s what they said.

In one week, almost 10% of the site’s users joined a Facebook Group called “Students Against Facebook News Feed.”

This prompted multiple apologetic blog posts from Zuckerberg.

But it also unveiled a deep irony. The group had only grown that fast because of the News Feed. Site engagement was exploding. Facebook users spoke loudly, but their actions spoke louder. Facebook stayed the course. Mark believed he was listening to what “users really wanted.”

This story reveals two hallmarks of this era of technology.

First, Facebook, through launching and getting user feedback, could iterate quickly. Zuckerberg’s users showed him that they wanted a News Feed. He did not need to innovate alone. His site’s data allowed for a conversation between builder and user.

But this moment also exposed the limits of that conversation. Web2 emphasized a specific user voice: quantitative data. The unique needs of a billion diverse internet users were flattened into the cold, monotonous clarity of numbers.

It was a step forward; the conversation was, after all, no longer one-way. But this step also created glaring deficiencies. We now live in an era characterized by the failures of that under-measurement.

A few of Arkive’s early acquisitions commemorate these failures. In Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Seduction, we witness how technology accelerates the commoditization of women’s bodies. In Aria Dean’s Eulogy for a Black Mass, we hear how viral memes are often dependent on the unrecognized and uncompensated contributions of Black culture.

Technology can change how we live. But it remains a tool built by and for humans. It reflects our culture and its power structures. Until we reckon with the failings of our human systems, technology will continue to reflect them.

The Web3 Era: New, Shared Myths

So what if rather than “changing the world” through technology, we started by changing the way we build technology? Rather than “garbage in, garbage out,” could we get “humanity in, humanitized-tech out”?

We can start by learning from the mistakes of our past eras. We need to abandon the myth of Prometheus once and for all. We need to imagine a new story where a community comes together to solve its problems.

That’s a major shift in our mythology. It’s like replacing Superman with the Avengers. It’s going from a lone genius to the genius of a diverse community. It’s remembering the truth that we go faster alone, but further together.

That’s a truth that our collective history supports. And it’s why I am so excited about Arkive’s first collection. The role of museums is to help us study our past to form newer, truer narratives. Who better to tell this story than Arkive’s Web3 community?

Already, we can see a more true, more representative story of technology in the works that the community has acquired. See, for example, the fans from Madonna’s iconic “Vogue” performance, which mixed Versailles-style costumes with a choreography popularized by Black and brown dancers, mostly in underground gay clubs. This acquisition invites a conversation about the line between inspiration and appropriation in modern culture. It does not answer the question, but it allows for dialogue about what a more fair creative future could look like.

And that conversation is, itself, a key innovation for our new era.

Web2 enabled a simple conversation between builder and market. Its holy grail was “product-market fit.” This was the moment when data revealed that the inventor had discovered a hit-product.

Web3 groups like Arkive enable a richer conversation between builders and stakeholders. Rather than looking for “product fit,” it asks builders to look for “community fit.” It starts with the idea that we should build a diverse community around a shared project. In working together, we arrive at more thoughtful, creative solutions than our predecessors.

When Arkive’s community comes together to tell a history of technology, they are more likely to tell a fuller and more nuanced story. To talk about who built the movements that spread technology. To talk about who profited and who was profited off of. To talk about the culture and the importance of context in all creation.

In doing so, it also completes the revolution from “users” as object-of-technology to “co-creator.” It reminds us that more voices do not have to slow us down. Community conversation, like data, is a tool for innovation.

That’s because it has never been technology vs. humanity. Every human pursuit is “technology.” Art, agriculture, industry, athletics, war—all are both inputs and outputs of technology. Technology is not a game changer, it is the game itself. We are all builders and creators. Humans are never content to accept the world as it is. We are always constructing something new.

It’s a lesson that even Prometheus learned.

You see, the myth of Prometheus does not actually end with him chained to the mountain.

When last we left him, the Titan was rotting on the rock and punished by the Gods for giving humanity fire. There he stayed for thirty years. Until, one day, Hercules came to visit. In Greek myths, Hercules represented the union of human vulnerability and divine insight.

To complete his 12 trials, Hercules needed to retrieve magic golden apples. These apples granted the eater immortality. To find them, and achieve his destiny, Hercules had to partner with Prometheus. The pair worked together to retrieve the apples. Hercules went on to glory. Prometheus was freed from his prison. Even in mythology, it is only through aligning with humanity that we actualize and liberate genius.