Mirrors and Mines: Digital Soul Searching

Ruth Gebreyesus considers Aria Dean's Eulogy for a Black Mass and its relation to media, identification, and blackness.

I find myself trapped in the vain and human project of seeking my reflection online. I am not alone, of course. I look for my likeness most on TikTok and the siren song that draws me in sounds like baile funk set to the visuals of a muted Congolese music video. Other times, it sounds like UK drill soundtracking a night out in Nottingham, where femme friends dress up like “mandem” while loitering on street corners, storefronts and masculinity itself. I do see my reflection in those videos. My algorithm must know my desire for gender collapse. It must know that I’d like to see national borders collapse too, pull at them using lines of mass displacement due to the transatlantic slave trade, due to colonialism, due to neocolonial liberalization, and so on.

“Historically, our collective being has always been scattered, stretched across continents and bodies of water,” writes Aria Dean in Poor Meme, Rich Meme, the antecedent essay to her 2017 video work, Eulogy for a Black Mass. Dean continues: “But given how formations like Black Twitter now foster connections and offer opportunities for intense moments of identification, we might say that, at this point in time, the most concrete location we can find for this collective being of blackness is the digital, on social media platforms in the form of viral content — perhaps most importantly, memes.” Since 2016, when Dean wrote those words, the opportunities and desires for intense identification remain difficult to resist and much content is being created from and for this desire. For me, and many others, seeking your reflection digitally can make an infinite algorithmic scroll seem like a mirror indeed—like we’re seeing ourselves, our nuanced complexities and intersections.

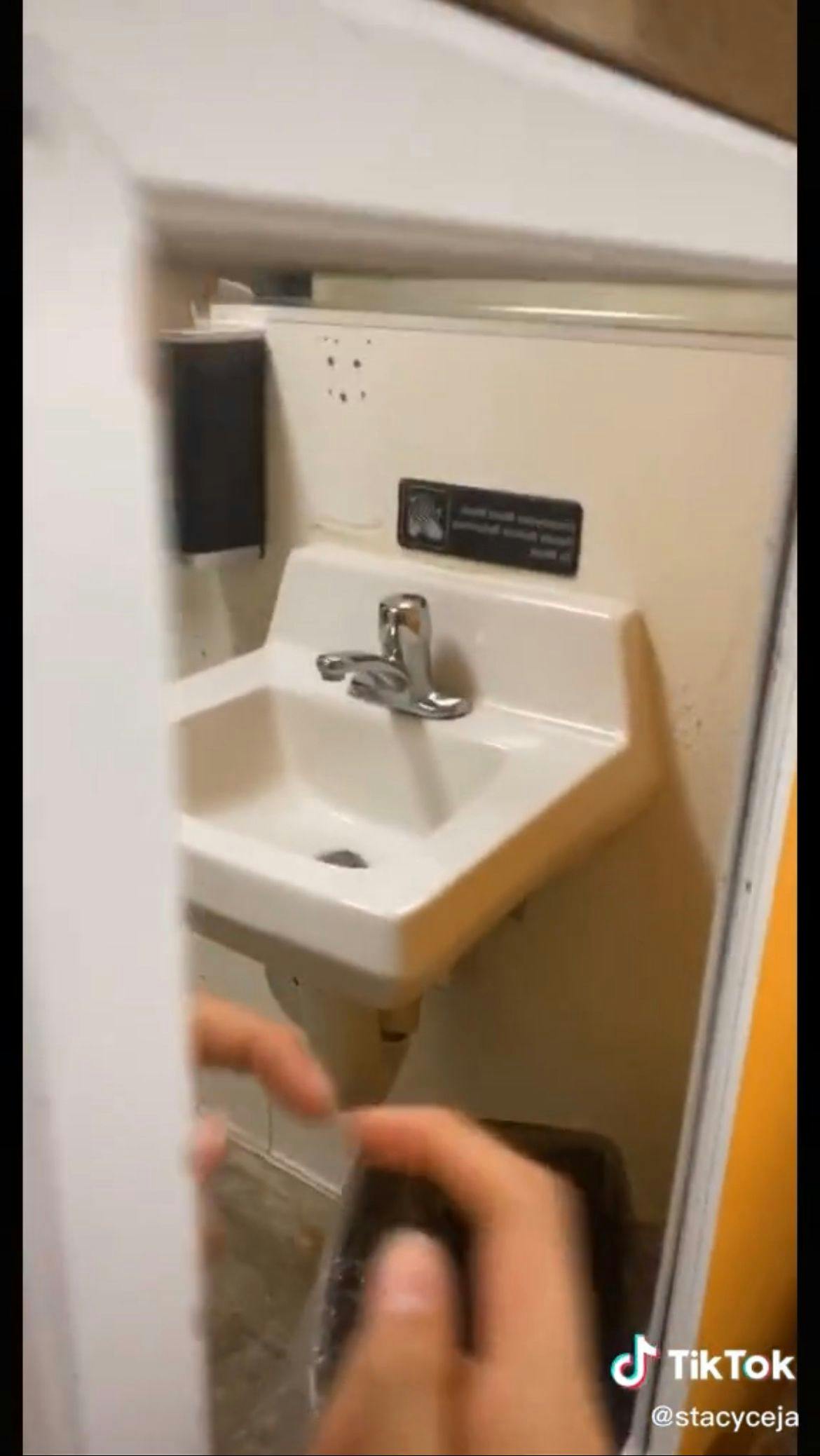

TikTok itself offers a true mirror test. In a meme format on the platform, users perform a perfunctory mirror test in transient spaces such as public bathrooms and hotel rooms. In one such video, a woman enters a restaurant restroom and aims her camera to show her reflection perfectly framed in an awkwardly low mirror across the room. She approaches and tries to detach it from the wall. It’s immovable. She then performs a test by placing her index finger on the mirror. If there’s an optical gap between her finger and its duplicate image, the test concludes that it is a true mirror. If her finger is able to touch its own reflection with no gap in sight, there’s a chance it’s a two-way mirror and she’s being surveilled on the other side.

If this test were applied to the app itself and the millions of reflections it holds, it would unequivocally fail on a metaphysical level. There is no gap between the reflections. Surveillance is uncontroversial, even essential to the platform. Like its meme-producing predecessors, TikTok has a reflective shine but is not a mirror. It is a mine.

In Eulogy, Dean soberly states, “Memes do have something Black about them.” A few cycles of life and of death since 2017, not only are memes still indelibly Black, sharing an ontology subject to circulation, but the platforms themselves are designed for and by that circulation. This is to say, the platforms' architectures are developing to have something Black about them, too. It didn’t start with Twitter’s reaction gif keyboards, offered up like emojis, but that was a significant moment when the platform shifted its shape to capture its users in more ways than one. The most viral—essentially, the most Black—content was mined for the dimensions that built the app’s features.

TikTok is no different. At this present moment in 2023, the platform is the most intensely hyperproductive social media app. Its reach is tremendous and global. Its meme output floods other apps. A nucleus in meme-production, TikTok’s dominance has likely to do with the fact that it is effectively designed for and by Blackness, for and by referential circulation. Black music, once crudely recorded on Vine and elsewhere, is now crisply uploaded and covered by copyright. Black voices, decontextualized from their sources, can now be the backing vocals to the actions of anyone, everyone. Black edits, sensibilities hard to track but undeniable to spot, are standardized akin to filters. TikTok is an app built by “the poor image”. The goal is to mine and capture, mine the capture and capture the mine so that production, and reflection-seeking, never cease.

“[These] actions in effect say, ‘we do not need Black people for Blackness,’” writes thinker and author Mandy Harris Williams about the Black mirage on social media. “The other side of this appropriation is social death, erasure and ACTUAL death.” It’s impossible to unsee how social media platforms mine Blackness, appropriate and circulate it, and even build infrastructure to accelerate this extraction so that Blackness without Black people can proliferate. Digitally, just as culturally, it is not necessary for a Black person to be visible, vocal, or compensated for Blackness to circulate. This sort of un-ownership, or universalizing, of Blackness can make it specific and ubiquitous at once. In contrast, and to Williams’s point, there are spaces where Blackness is easier to define, legislate around, fence in, and even decimate. In “the uneven distribution of death across a social field” as Saidiya Hartman terms racism. “The vulnerability to premature death,” she elaborates.

Since Eulogy, Dean’s shifted her attention towards what she’s termed the Black generic, a possibility fracturing out from the dialectic tension between Black representation and abstraction, particularly in photographic images. The burden to portray the Black collective or individual accurately, whatever that may mean, or to abstract in fugitivity, can be wearing. “[The] black generic operates from an acceptance of the implicit ‘consent not to be a single-being’ involved in black existence and aims to draw out and image this condition,” she writes. “The black generic forms that ‘middle ground between the One-All and singularity and individuality,’ and accommodates both the discrete and the continuous, the individual and the collective identity.”

Dean implies that social platforms, and their disjointed and framed posts, might be ripe to explore a passive form of the Black generic. I think that’s what keeps me searching for myself on TikTok. Not the most viral content but the anti-viral moments, sometimes within the meme itself. Hyper-regional and colloquially specific almost to the point of illegibility. A young man appears with his hair freshly twisted and speaks of this event in a Baltimore accent too thick for outsiders to comprehend or even believe. Sometimes it’s truly nonsense. A non-sequitur uninterested in finishing the path it started. A person waters the median greenery in Abidjan from the back of a truck. They’re filmed by someone inside of a car whose turn signal flashes quickly on and off again. I don’t know why I’m looking, but I know I like it.

@Stacyceja on TikTok.