Is TikTok My Analyst?

At first, it was weird; then, it was boring. The TikTok algorithm kept serving me—a gay Chinese American male—videos of hot girls drinking coffee, or singing along to pop songs in the car, to which I’d spasmodically scroll up, perhaps a touch too quick, to train the algorithm that I wasn’t interested. Except it wasn’t working. While my Instagram reels (e.g., hot guys at techno clubs) seemed to know I was gay, why wasn’t TikTok getting the picture? In one sense, it did. One night, I got served a clip of young female couples making out at various cultural landmarks worldwide: the Eiffel Tower, the Great Wall of China. Oh, I discovered. TikTok thinks I’m a lesbian.

We barely knew each other. About a year and a half ago, I first downloaded TikTok, a user-generated video roulette app, to destress my life with ASMR videos: girls—always girls—whispering sweet, soft nothings while they sprayed whipped cream on a Saran-wrapped microphone. From the start, TikTok felt wholesome but tinged with perversity. Something about the bite-size content was just as stimulating as a Diet Coke yet as inebriating as a beta-blocker. The app could surprise me. After a round of sound bowl healers, the algorithm stoked my paranoia with CCTV footage of humanoid aliens crossing freeways but then washed it all away with a dog staring into the ocean—a pattern that presented its videos as the sole solution (balm) to a problem it created (anxiety). It told me something about allure and control: it’s not about content but rhythm and timing.

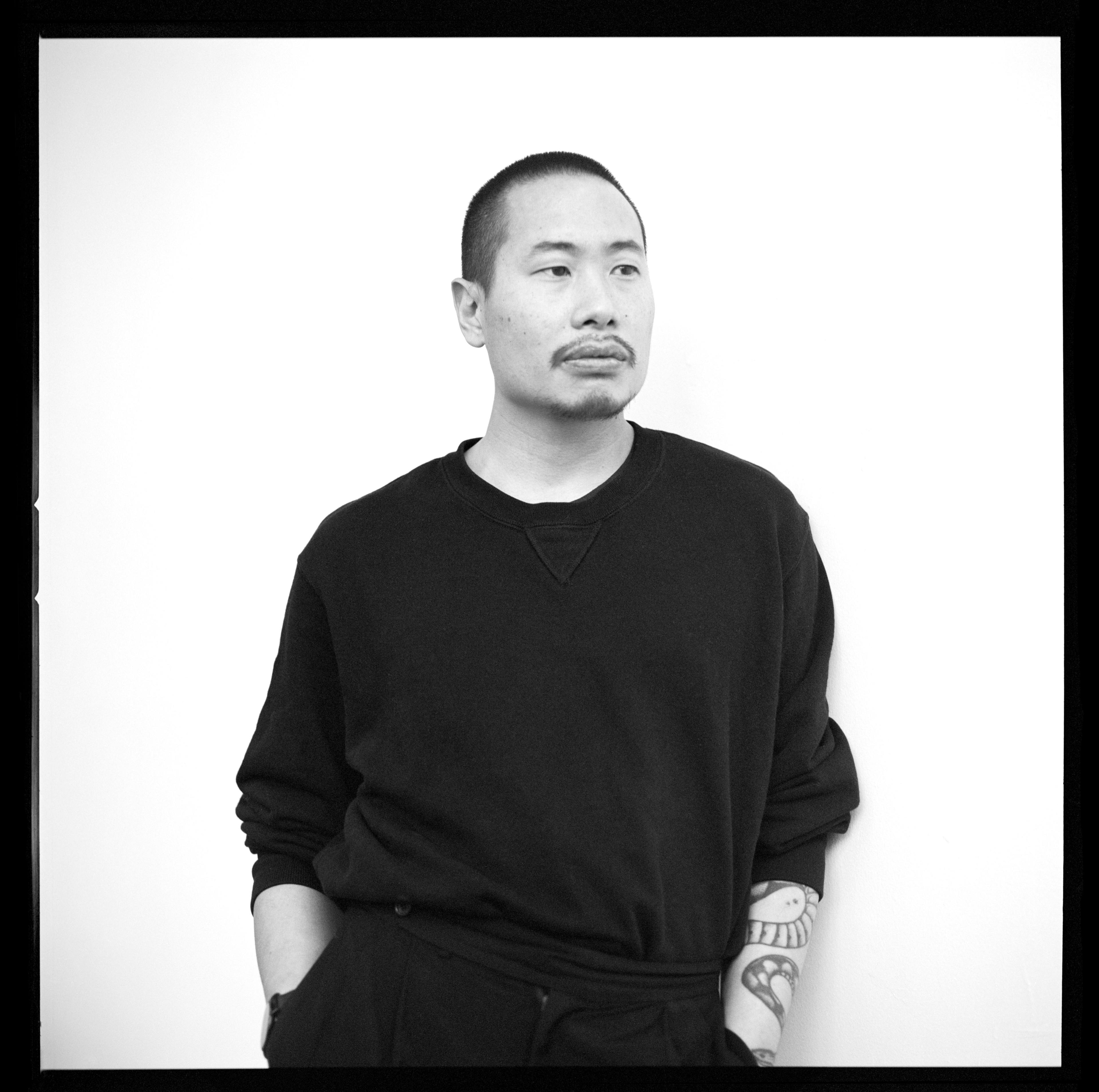

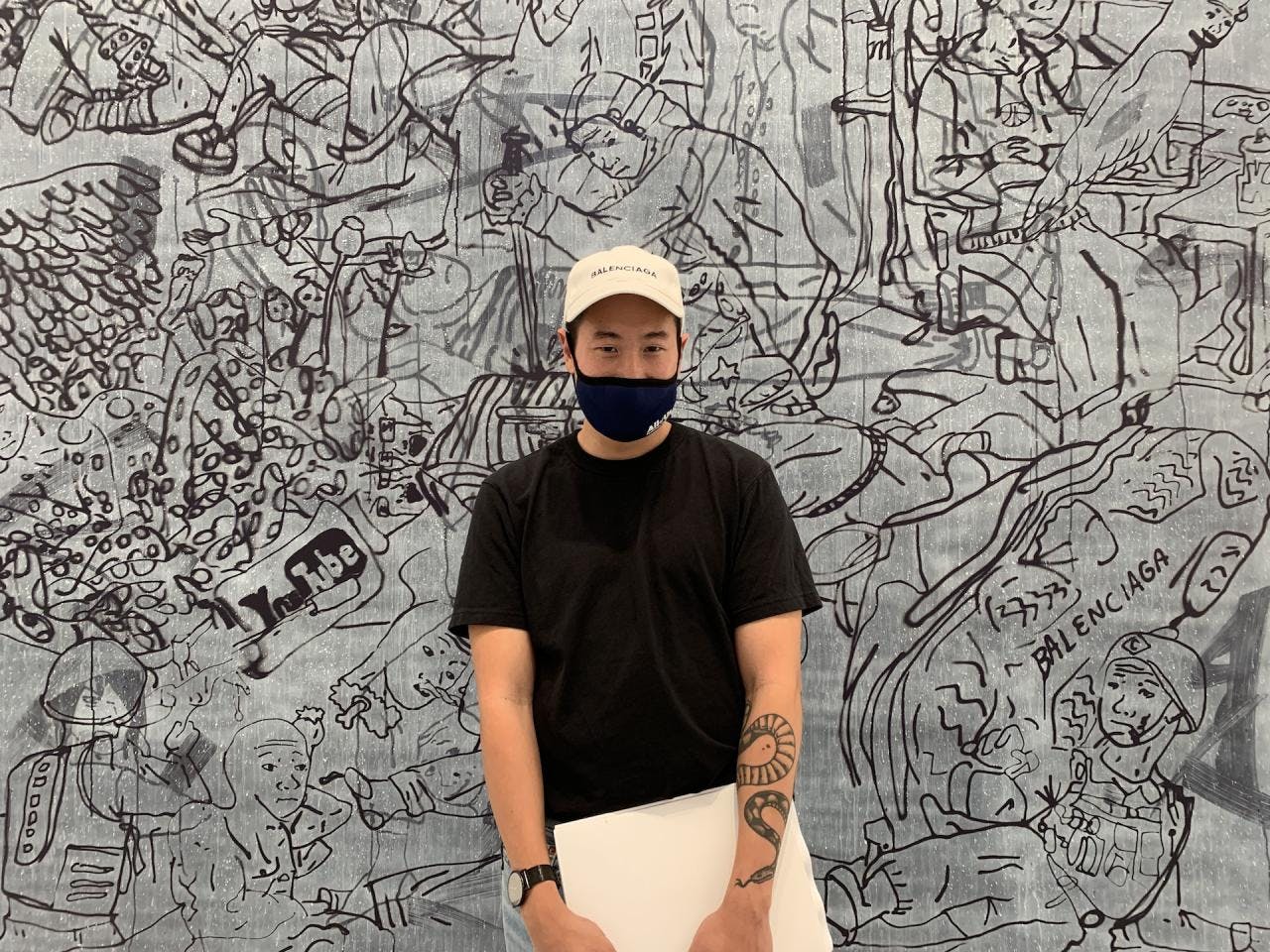

It was winter in New York, and we were falling in love, my screen and I. The algorithm obediently archived my psychographic data: preferences for Cirque du Soleil and tattoo artists with acrylic nails, search histories for impressions of Julia Fox. Like a stalker recording when I entered and exited my building, it logged my watch times. Anyone walking past my bedroom door those nights—as I lay in bed, lights off, eyes wide open, cackling myself to sleep—would’ve thought I was going insane.

Eventually, the algorithm started sending me videos of what I really wanted. (“For bottoms and twinks only,” a shirtless Midwesterner says, glancing down at his trunks. “Let me know if you want me to lay some pipe down.”) Then the hot girl content introduced a different kind of subject: Girls wrapped in feather boas, girls in five-inch stripper heels, pre- and post-op girls, girls in eyeliner and mustaches who blew kisses to the screen, contestants from RuPaul’s Drag Race, some who weren’t girls at all but could be if I agreed to believe them for the fifteen seconds before the Repost button showed up.

Was I training the algorithm, or was the algorithm training me? These girls didn’t turn me on, but my algorithm seemed to suggest that I wanted to see them. These girls took control of their image, were unafraid to confuse, beguile, or even lock eyes with the camera phone and demand to be loved. These girls touched something deep inside me. To be a hot girl meant to command desire. I could not look away. Eyes closed, I thought of my frustrations with love and sex as the algorithm seemingly whispered in my ear, nobody knows you like I know you.

“I think my TikTok thinks I’m trans,” I said one night to Pujan, an art historian, at a loft party in Tribeca. Across from me, I could see a Wade Guyton painting hanging from a removable wall.

“Do you agree?” he asked.

“I don’t know.”

He told me about an argument he had gotten into with his analyst about an interpretation he disputed. Typically, Pujan shows up to his analyst’s office multiple times a week and lies across a couch, spewing on about his life as they parse through the drivel of Pujan’s utterances, projections, and desires. During a recent fight, the analysis touched a sensitive core, and Pujan lashed out—yelling about how the analyst’s interpretation or advice from the previous session was totally wrong, even reckless. His analyst, a trained professional, was paid to take it all silently.

This is typical of the second stage of analysis. According to the Freudian and Lacanian traditions, there are three stages of transference. In the first, the analyst barely says anything as he tries to figure out what authority figure you're projecting onto him. Slowly, the analyst will observe, take notes, and then start acting when he's ready—playing the part of the projection. Let's say it’s your father. The analyst will try to perform the figure of your father, what he approves of, and how he shames and rejects you. This is supposed to be so magnetizing that you ache for the approval of this charming intelligence who has bestowed his attention on, of all people, you.

The second stage is when the transference flips. Suddenly combative, you rebel against your analyst like a teenager. You may think this is refuting the authority of the analyst/father, except that rebelling reinforces their power position in your life: the locus you define your life against. With my last analyst—a woman who wore black turtlenecks like a Manhattan architect—I had gotten to the second stage disturbingly fast. On two occasions, I dreamed of her standing in a classroom, yelling at me. I had to end it.

Except now, there was a new analyst in my life: TikTok. Several times a week, I sat with my TikTok, spending one to three mindless hours on the platform as it silently took notes on my subconscious. Once, I got served a video of a blonde boy in glasses. “I’m making two videos. Whichever one you get is what the algorithm has you classified as,” he says. “If you get this one, you’re straight. There’s no punchline. If you get this one, you’re actually straight.” (The second video ends, “You’re straight. Straight up gay.”)

The very next video: a shirtless construction worker in a hard hat, six-pack, and hairy chest, arranging metal beams in a grid. Oh, fuck off.

Now, if I got served a video I didn’t like, I would close the app like I was punishing it. I was locked in stage two of the transference. The mind games were getting under my skin. Did I secretly agree with it? I tried deleting the app but downloaded it again two days later. I couldn’t get its voice out of my head, which seemed to whisper, I know you better than you know yourself.

The problem wasn’t whether or not TikTok was right about me. If I was or wasn’t trans, I wanted the idea to come from my queer community or me, not from some AI quietly brainwashing me with one video after another. While gender identity is an opportunity for solidarity and collectivity, TikTok treated it like shopping, as if I could choose from a menu and pick which hot girl I wanted to become. This wasn’t about discovering one’s gender identity. This was narcissistic consumerism.

In 2022, TikTok made ten billion dollars in revenue. Across the globe, the app entertained one-billion active monthly users. For the first time, a Chinese-owned app had dominated America, and it had the US government spooked. The New York Times called it “a Trojan horse—for Chinese influence, for spying, or possibly both.” The director of the FBI told Congress he was “extremely concerned” about the app’s operations in the US. The military barred the app from government devices. The White House blocked its staff members from downloading the app.

While the current scare in Washington over TikTok is targeted at its data mining, TikTok’s danger, to my mind, is more nuanced and quotidian than that. Likely, what I was experiencing could be happening at a civilizational scale.

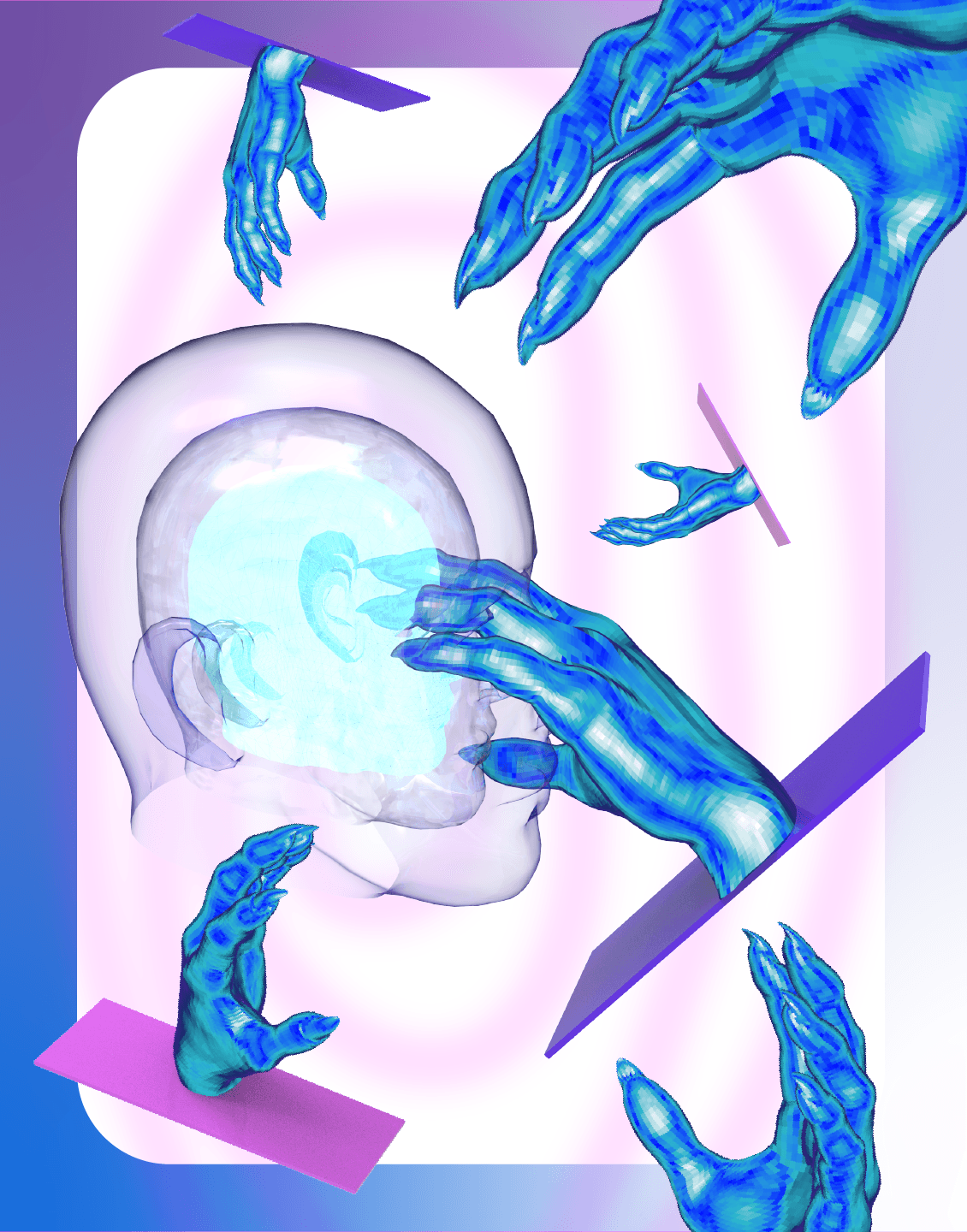

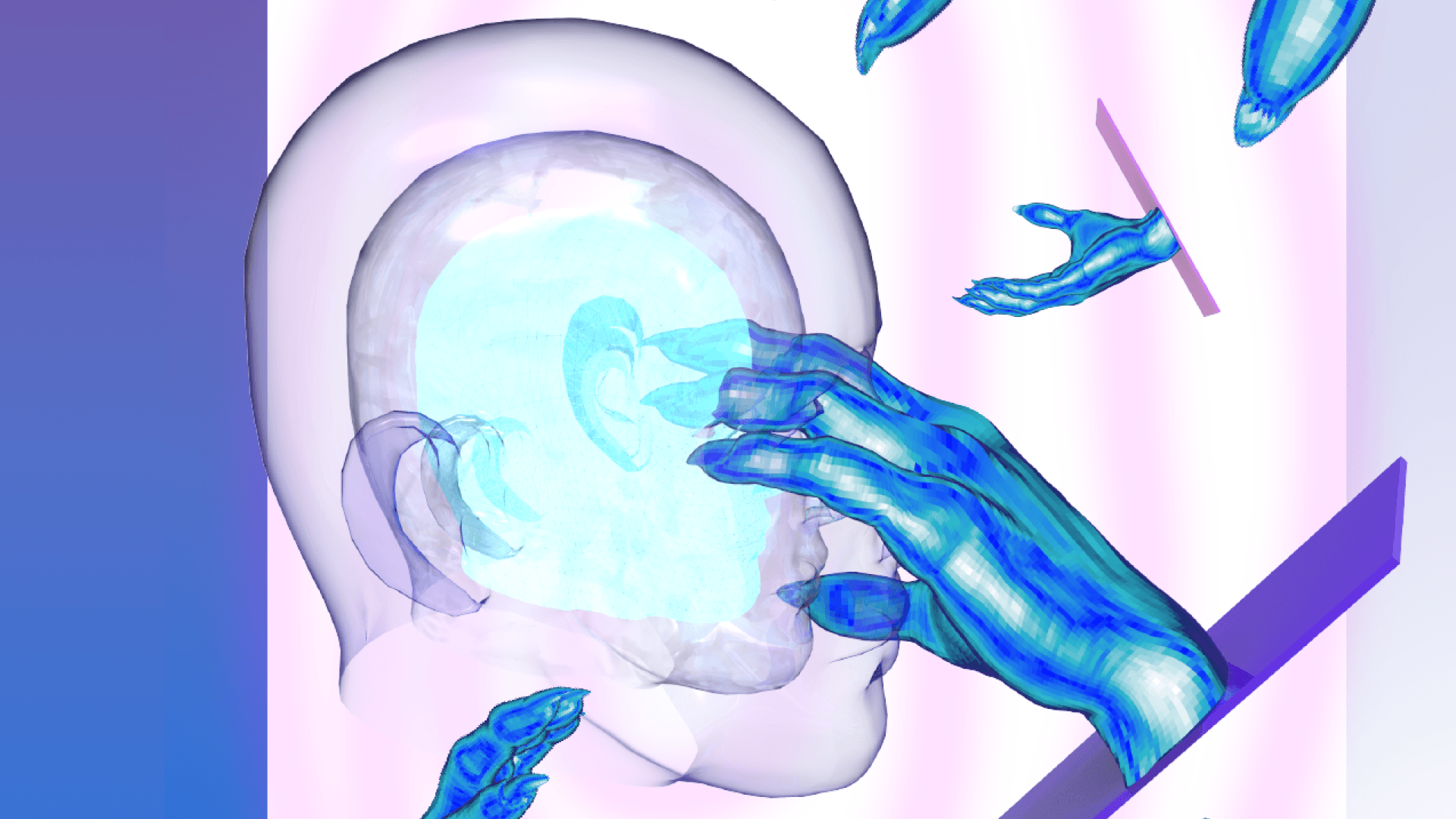

I’m talking about AI-induced transference. TikTok seems to have direct access to users’ subconscious, which should be the purview of licensed professionals. Psychoanalysis is a consensual and highly artificial relationship conducted by humans, many with medical degrees, with the goal of transforming the analysand’s relationships and their latent desires. Except TikTok plays this role with obscure goals in mind. One internal document titled “TikTok Algo 101” rates goals along scales of “user value,” “long-term user value,” “creator value,” and “platform value,” which operate on a trove of collected data so detailed and complex as to appear mystical. By masquerading as a supreme intelligence, the app baits users to project some God-like authority onto its algorithms, giving it the power to transform their senses of self, relationships, and desires, just like it did mine.

What would it mean for a machine, profit-driven intelligence to be active in forming a collective, global subject?—a billion of us, shaped by machines as we nightly stroke our screens. The goal of TikTok’s algorithms is to generate value. By shaping us in its image, it trains us to accrue value on our own, financial or otherwise, in a late capitalist regime that has made a total commodity of the individual. This precludes collectivity or community. From the beginning, what distinguished TikTok from earlier social media was its lack of social—no one ever meets anyone else on TikTok. We’re endlessly engrossed by our private realities, illegible or merely comic to outsiders, which is the beginning of insanity.

But here’s the third and final stage of analysis: When the analyst offers interpretations that just roll off you. You don't care. He could say anything provocative or triggering, and you'll reply, “I know why you said that, but it’s neither here nor there.” This suggests that you have completed the analysis. You have defeated the father; overcome the Other. Both you and your analyst will mutually detect this is happening, and eventually, you and he will lock eyes, nod, and say, “You know what? We’re done here.”

Ideally, I see a world where I live with TikTok in casual indifference—perhaps where I am now with Facebook (I log into it twice a year to find subletters, and it’s reliable). Eventually, I might leave TikTok alone, not with spite or nostalgia but unfazed indifference. Attempts to ban or deactivate it from my life only further enmesh me in its psychic power games. For now, I try to stay wary of projecting more power and meaning into its opaque opinions. Guessing why TikTok thinks I’m trans would effectively do the work for TikTok and fill in its cryptic silences with arguments of my own making, which will, in turn, convince me because they feel like they have come from within when in fact they have not. But rather than deny TikTok’s existence or refute its intelligence, I can acknowledge its presence somewhere in my universe and choose to do nothing.

Like I do now. I still get served the hot girl content these days, but it doesn’t hit me like it used to. Like the one sitting on the window of a fire escape, looking over her shoulder, blonde hair blowing. Her monologue about New York City has a touch of self-aware performativity, to say she’s in on the joke, which takes the edge off her self-indulgence. She doesn’t quite look straight at the camera, only askance, so I can’t get a read on her. She’s an empty container for the algorithm to inject words in her mouth as if saying to me, and only me, what if this was you?

Carefully, I close the app.