A released soul in online form: the evolution of the profile picture

Everywhere we go on the internet, we leave behind digital footprints. When I first heard this phrase, I thought: Why not fingerprints? The cursor is, in effect, an extension of our fingers. Imagine every click is a tiny arrow print stamping into the digital ether. But lately, I’ve been thinking about the prevalence of faces on the social internet. Our profile pictures are our “face prints,” so to speak, and our likeness is often one of the first things demanded of us. We can, to an extent, scrub our footprints—but what of our faces? Is it too late?

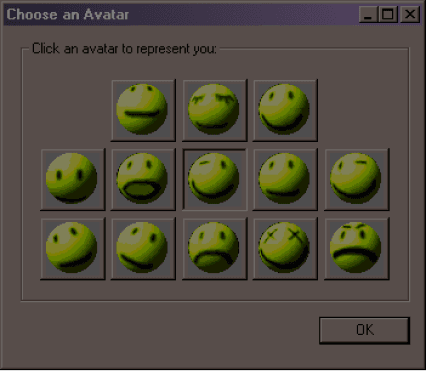

When I think back to my early days online, I’d be hard-pressed to remember the first name of anyone I interacted with, never mind their face. Identities were affixed to screen names — a sequence of nonsensical words, catchphrases, and letters, haphazardly capitalized or appended with a string of numbers. Avatars were our virtual stand-ins: highly pixelated, low-resolution images that represented our humanity in cyberspace. (The term was adopted from Sanskrit in the 1980s by video game creators and science fiction writers, before becoming subsumed into early internet culture via forums and chat spaces.) Avatars were fictive symbols. There was no presumption of reality in what they represented. The first avatars on The Palace, a visual chat server, were essentially free-floating emojis: tennis balls with facial expressions.

The first avatars on The Palace, a visual chat server, were essentially free-floating emojis: tennis balls with facial expressions.

Two decades ago, the human face felt unnecessary. Today, we can’t imagine, nor can we trust, online interactions without it. A face was once not only an over-share, but a potential liability for itinerant users, traversing across cyberspace. Anonymity was not just the norm; it seemed to be the prerequisite across role-playing games, forums, blogs, and chat spaces. Harassment was casual and rampant, but even the violations felt less personal and more random without a face affixed to either assailant or victim. A user’s identity was fluid to a fault. Avatars and screen names varied by platform.

This changed with the arrival of Facebook. MySpace cracked the anonymity dam, and with the advent of social media, the enmeshing of our offline and online identities was complete. New terminology emerged to replace it: picon, userpic, profile picture. The formal “face card” was introduced, and avatars became gradually phased out in Web 2.0. With it came the expectation that users would upload portraits of their real-world self.

Upon its arrival, the profile picture was monumental. Here was an occasion to upload a photo of yourself that announced to the world who you are. In the MySpace era, people spent hours staging flash-blinded photoshoots in front of the bathroom mirror. There was a behind-the-scenes sleaziness to the MySpace pic that dissipated as people moved to Facebook. The user’s face would typically be concealed or out of focus. Most of these photos were taken without peering into the viewfinder of a digital camera, and the emphasis was on the outfit or the contours of a person’s body. (For men, shirtless pictures were common.) On Facebook, however, photos were staged more properly. Front-facing cameras made it easier than ever to take better selfies. Our well-lit faces have since become the primary basis for identification across social media. The profile picture is a unit of communication that confers and confirms personhood. It imparts a sense of social legitimacy to a user’s profile. Our frozen smiles exist to telepathically assure virtual onlookers that we are real people, that we are worth paying attention to.

From the "Selfie" music video by Chainsmokers.

“The selfie is phatic,” the critic Brian Droitcour asserted in 2014. The selfie, in its most public iteration, is a profile picture. It becomes a personalized emoji of sorts, an image “that establishes immediate contact by introducing gesture and mimicry — both components of facial interactions — to communications.” Unlike portraits, which connote import and status to the featured person, the profile picture-selfie “inscribes [the user] to the networked present.” It’s a statement of one’s virtual presence that anticipates a response. It’s an invitation to connect and follow, to look and like.

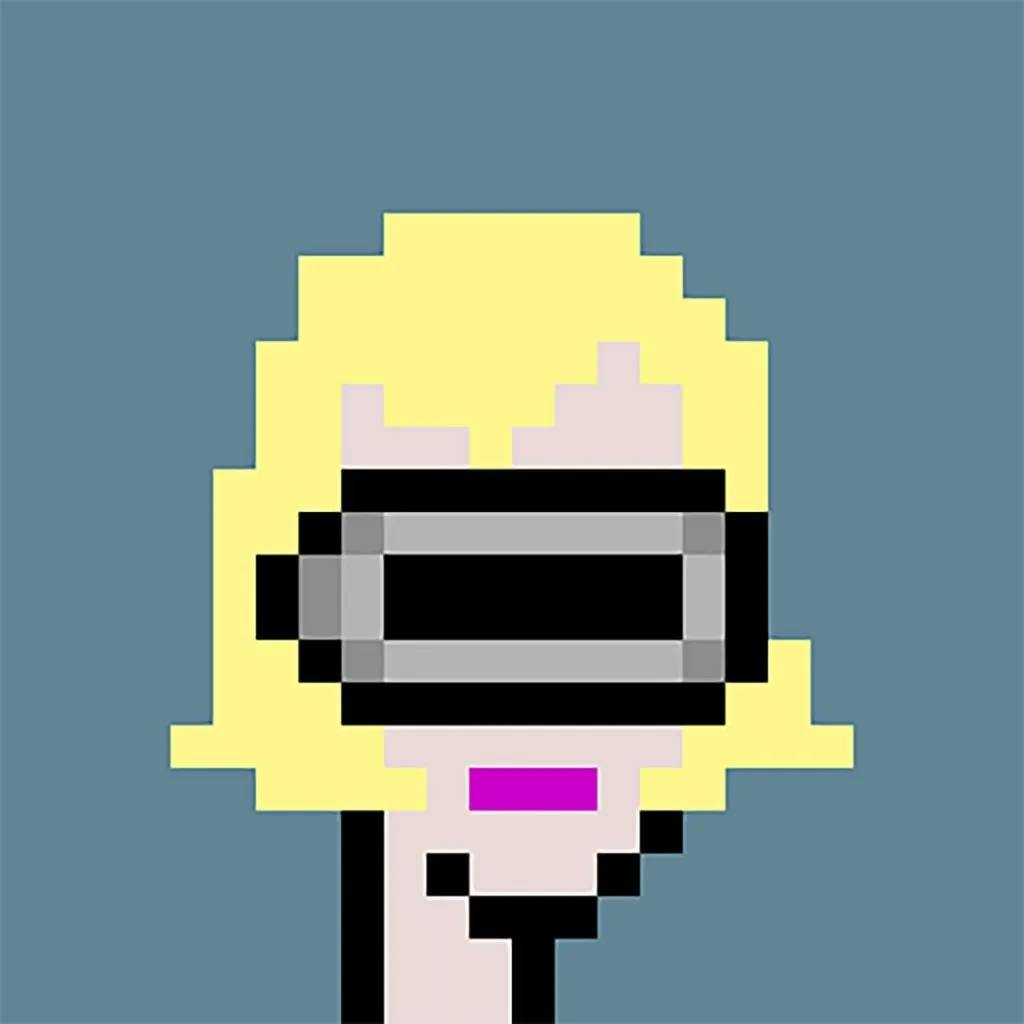

As part of its metaverse initiative last year, Meta began rolling out avatars. These are Bitmoji-like, 3-D cartoons that are supposed to be our virtual reality stand-ins, but I don’t know a single person who has created one. In January, Meta introduced a new Instagram feature that lets users alternate between showcasing their profile picture (presumed to be an image of their face) and their avatars (a cartoonish version of their face). The avatar will be animated, and viewers can easily toggle between the two. It’s a small update, but it highlights the growing schism between the two, once-synonymous terms. We associate profile pictures with an authentic representation of ourselves (Web 2), whereas avatars can be more fluid, allowing for a form of “variable selfhood” to emerge. The avatar, then, is the visual token of a decentralized internet (Web 3).

With Web 3, an individual’s online identity can be entirely severed from their real self. Their personhood can be determined and confirmed by other metrics: a crypto wallet, for instance, rather than a social media profile. Visual identification can thus deviate from the face, towards more abstracted forms of self-expression. Meta and other social platforms have been keen to capitalize on the Web 3 hype by introducing hexagon-shaped NFT profile pictures and avatars. But these interface changes are antithetical to the notion of a truly decentralized internet, so long as users’ identities (and faces) are affixed to a central profile. However, it’s unlikely that users will be comfortable giving that up. It would be jarring to return to an amorphous, face-less digital landscape — and impossible.

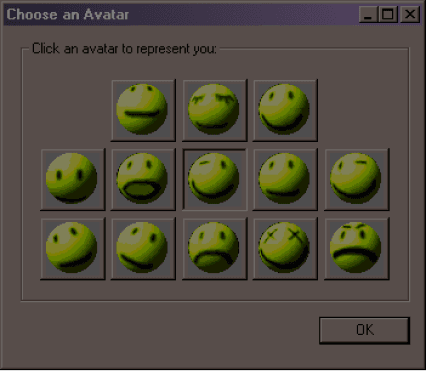

Enter: the NFT profile picture, or PFP, a playful proxy to the avatars of yore.

During the 2021 NFT boom, crypto collectors retired their faces for brightly illustrated, cartoonish, anthropomorphic PFPs. There were plenty of projects to choose from: CryptoPunks, World of Women, Bored Apes, Cool Cats. These images became collectible status symbols and whimsical alternatives to traditional PFPs. Many embodied the lowbrow aesthetics of the early internet with an emphasis on pixels, constrained color palettes, and two-dimensionality. Illustrated PFPs have remained prevalent, even throughout last year’s crypto winter when prices of PFP projects were volatile. For non-collectors, too, the traditional profile picture seems to be receding in relevance. So is this elusive notion of authenticity, undergirding one’s “personal brand.”

CryptoPunk #305 (featured in the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami)

Since the pandemic, I’ve noticed that fewer and fewer faces have been showing up on my Instagram — not just on the feed, but in my Stories header, with its endless queue of gradient circles. The same was occurring on Twitter. There were fewer familiar faces, and more objects, illustrations, or recognizable images from pop culture: a white stuffed bear; a chibi anime character; a Georgia O’Keefe painting; a bonsai tree; a pearlescent orb. Recently, I have changed my Instagram profile to Edouard Manet's painting Berthe Morisot with a Fan. It’s of a seated woman concealing her face behind a black handheld fan. Her eyes, peering through the sticks’ slits, look distorted. I found the image to be an apt metaphor. The woman’s obscurity reflected my resistance to the perceptive predisposition of a regular profile picture.

After a decade-plus of showing face online, people are now turning to objects, creatures, or art to convey their digital essence. Yet, we’ve grown ever more accustomed to human features and faces, even computer-generated ones. Our brains are predisposed to consider human-like avatars with “greater social potential,” according to one 2013 study, compared to static, two-dimensional avatars. We perceive avatars and similar profile images as social entities; we categorize them in accordance with learned stereotypes and heuristics. Virtual spaces are not immune from the transference effects of the real world, but our online identities are significantly more mutable.

“When we step through the screen into virtual communities, we reconstruct our identities on the other side of the looking glass,” wrote Sherry Turkle in her 1995 book Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. It makes sense for our profiles to reflect this shift, from a centralized social internet to decentralized, pseudo-anonymous communities. We are, in a sense, back where we started. But by no means is the evolution from Web 1 to Web 3 circular, nor are we exactly in a post-profile picture landscape.

The slow regression towards more facial anonymity has coincided with the rise of deepfakes and AI, against the backdrop of an internet that is increasingly run on computer-automated activity. The “dead internet” theory was once a fringe, deep-web conspiracy that bots, having outnumbered humans, have killed the internet. I used to balk at that claim, but it has only felt truer in recent years. Another day, another bot account finds me on Instagram. YouTube traffic and comments are consistently swarmed by bots. When I need help with a service, like a bank, online, I’m almost always routed to chat with an automated service representative.

Twitter profile picture evolution.

The mainstreaming of AI tools like ChatGPT, MidJourney, and Stable Diffusion has contributed to this overwhelming feeling of fakeness. How can we tell if the people we’re interacting with are real, when their faces can so easily be faked?

There was a week or two last winter when everyone was fawning over Lensa AI, an app that generates lifelike portraits of users. People paid money to upload a few selfies, and Lensa worked its magic, spitting out high-quality digital portraits that were extremely eerie in their likeness. Some people used these renderings as profile pictures. It was their face, but it also wasn’t. Lensa fulfilled a narcissistic impulse. People were drawn to the app because it offered them some fantastical flexibility over their image. They could look like a warrior princess, a superhero, a sexy elf. It was also fun to play with. Either way, the proliferation of AI image generators like it means that we can now produce human-like faces on demand.

Even as the decentralized internet offers us some anonymity, our features, with the help of AI, can be accurately rendered and replicated onto realistic avatars. It’s part of the trade-off we made long ago when Facebook introduced profile pictures. In the uncanny valley, our faces are no longer our own.

Meta bitmoji.