Epistolary Purgatory

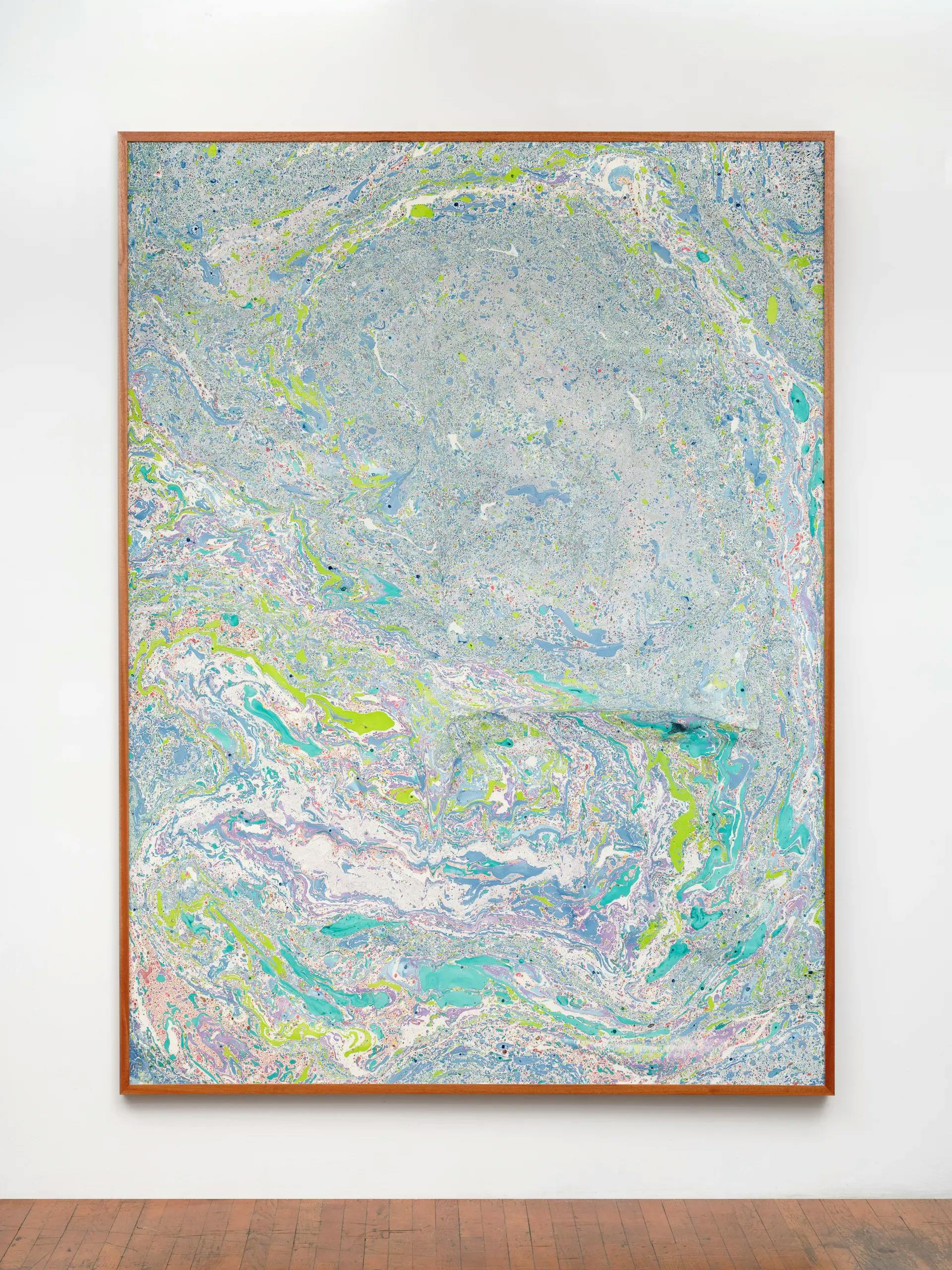

Picture a cosmic illustration: pastel streaks of the Milky Way with stars dropped in, gently sucked toward a void. Transmute this into a scientific slide: a cross-section of muscle tissue, striations and pockets dyed according to some undisclosed principles for legibility. Dissolve this into a natural landscape: pond life in early spring, the algae populating the surface stirred by some chemical fizz.

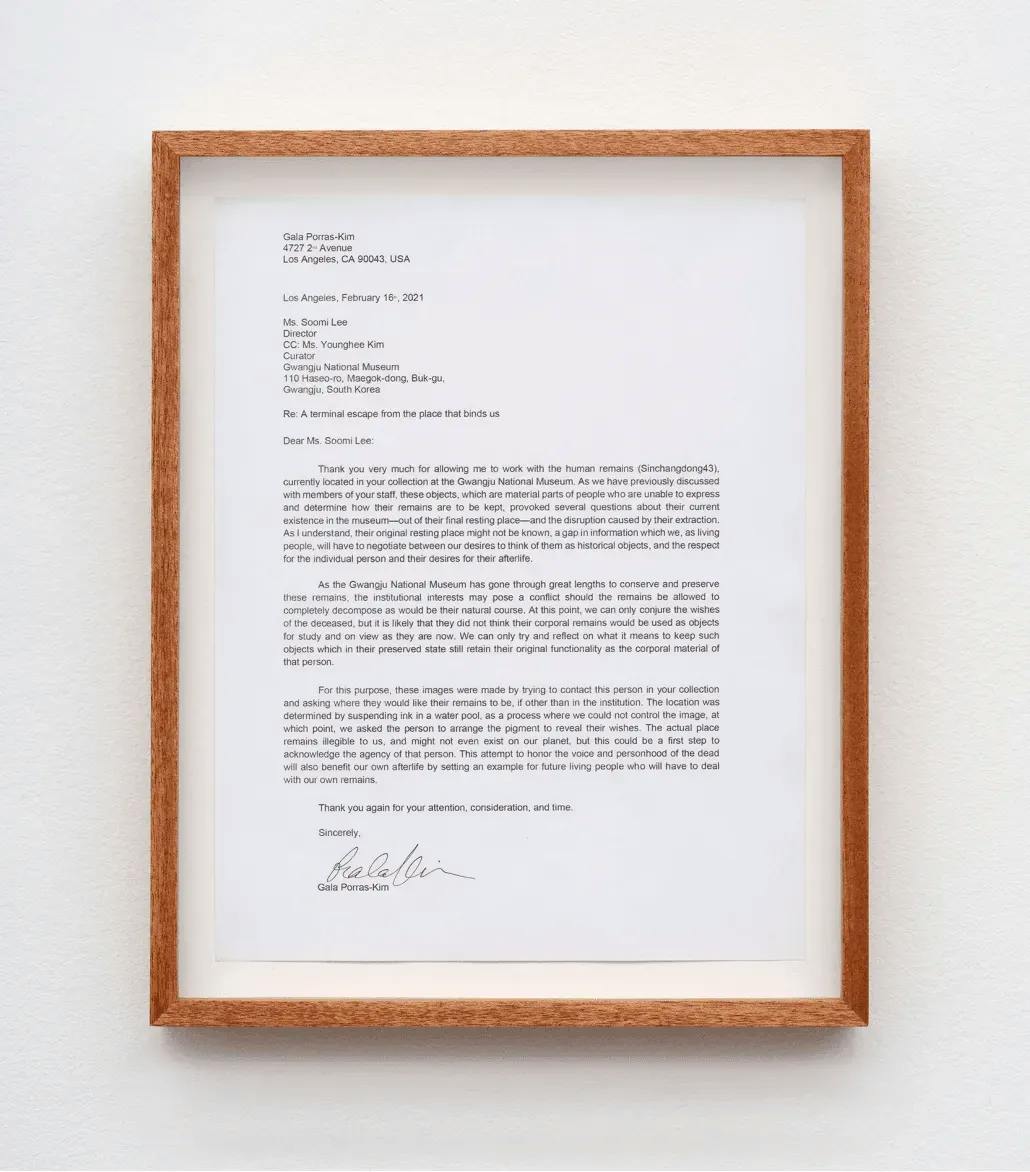

These images come to mind in front of an abstract work by Gala Porras-Kim, a sheet of marbled paper dominated by light blues, grassy greens, and healthy pinks. Marbled paper is often encountered on the inside covers of old books, where it initiates an intimate reading experience. Porras-Kim’s piece instead dwarfs the viewer at more than eight feet tall and the only language it precedes is a nearby letter—similarly hung in a minimal teak-colored frame—that completes the work, titled A terminal escape from the place that binds us, 2022. The letter is full of hard and contrarian words: unable, provoked, final, disruption, original, information, terminal. The letter is also full of invitations: conjure, negotiate, think, reflect, honor, set an example. It speaks of desires.

A Terminal Escape from the Place that Binds Us, 2022. Ink on Paper. 97.5 X 72.5 X 2 in. Acquired January 2023.

The letter, written in 2021, is made out to Ms. Soomi Lee, director of the Gwangju National Museum, and concerns the remains of two humans that were recovered from a shipwreck. When a letter is shown in a museum, one might initially expect that it is material from an archive. But Porras-Kim’s correspondence is more self-reflexive; it questions who holds archives, how and why. The artist suggests that the removal of the remains from their prior site and their display at the museum has disrupted these particular humans’ desires for their bodies after death. She claims to have invited these humans to communicate about their preferred resting place through the process of creating her marbled paper work. “The actual place remains illegible to us,” she notes, “but this could be a first step to acknowledge the agency of that person.”

Porras-Kim’s letter states that these humans would likely protest their present circumstances. This would be understandable—without the protection of flesh, the context of a life, or the dignity of a ceremony, many people would object to being so vulnerably and indefinitely on view after death. It is also possible, of course, that these people would have been delighted to be displayed in a museum as the sole representatives of their society in their time, just as people today might donate their body to science to give it some greater purpose. Perhaps to be preserved by a team of experts and showcased within a larger human history would have been understood as an achievement of immortality or power. It seems unlikely, anyway, that these people intended to die in a shipwreck; their other plans had already been disrupted.

A viewer might also question whether Porras-Kim indeed established communication with these humans. Perhaps we don’t believe her because there is no key to understanding this image that supposedly represents their exchange, or because the image is too beautiful or too familiar to be understood as a supernatural transmission. Where is the proof? Now we are talking about faith. What is faith as it functions in art, setting aside representations of faith and the faithful? Often, what is mysterious about art is not the process by which it was made but what is withheld or implied in its appearance before us—and that is precious. That, we might want to leave unquestioned, for that is what holds us in front of the work.

Untitled (1990), Tom Friedman. Two identical sheets of papers, each 11 x 8 1/2 in.

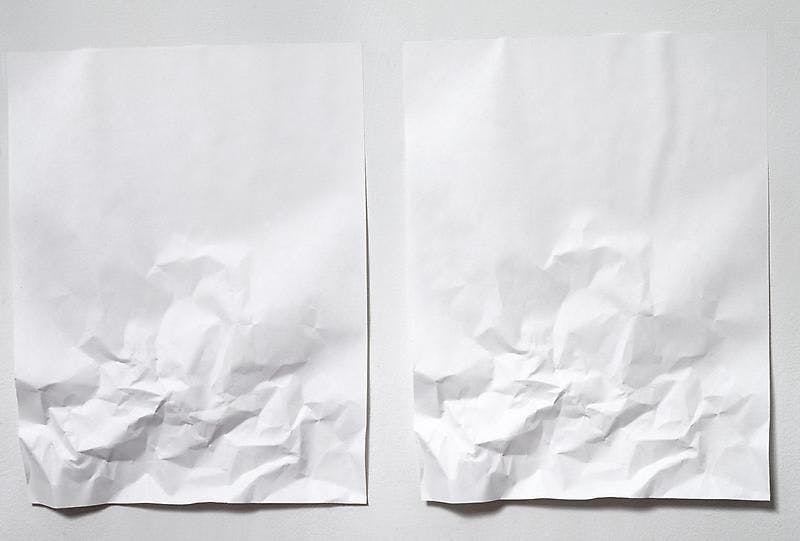

Consider another paper diptych, Tom Friedman’s Untitled, 1990. Side by side are “two identically wrinkled sheets of paper.” After reading this medium description, on examining the carefully placed hills and valleys of each page, one marvels at the artist’s ability to fold one just like he folded the other. “What care went into this, what precision!,” a viewer might think. But of course, the artist simply folded the sheets simultaneously, as if a single sheet, and then separated them into a diptych. Still, the mental exercise of studying minutiae persists, and it is the impression that something more complex is at work that makes it compelling.

Here Lie the Secrets of the Visitors of Green-Wood Cemetery, (2017-42), Sophie Calle.

Or consider another, equally mortuary set of seemingly one-sided exchanges, Sophie Calle’s Here Lie the Secrets of the Visitors of Green-Wood Cemetery, proactively dated 2017–42, a project for which the artist invites visitors to write down and bury “their most intimate secrets,” marked by an obelisk in the titular graveyard. In withholding visitors’ answers, Calle encourages people to both disclose the untold to unknown future readers and to imagine whole worlds of yet unshared stories.

Though she encourages us to believe her, Porras-Kim does not assume that we could understand or deliver on whatever requests these humans may have communicated. She has noted that the human ancestors she engages throughout her practice probably participated in entire belief systems and languages of which we have no conception. Instead of a specific proposal, the marbled paper seems to serve as a shallow space for contemplation and interpretation, like a cup of tea leaves or a reflection pool. As visitors, we project our own concerns, assumptions, questions, and understandings onto this sheet. What kind of dialogue is possible with our predecessors? How would we meaningfully record our own desires and consent for humans who might find our bodies in the future?

The process behind this work, Japanese Suminagashi (“ink floating”), has been practiced at least since the tenth century. A maker squeezes drops of ink into a bath of water, strategically pouring, gently shaking, or raking the pigments to produce surface patterns. Paper treated with a coating is then briefly placed on the surface of the water to capture the ink patterns. Historically, the resulting paper would sometimes serve as a semi-abstract illustration, as when it was used for several pages of a 13th-century copy of the Japanese classic The Tale of Genji that discuss the sea. In front of Porras-Kim’s work, imagining this ink floating in a temporarily held pattern introduces the sense of a hovering presence only briefly settled before us. One could draw connections here to any number of mystical practices and spiritual visions, even the childish delight of a Magic 8 Ball.

But in A terminal escape, despite the finality implied by the title, Porras-Kim provides no answers, no revelations. She places her viewers and the museum in a position of suspense—we wait for some illumination—without any promise of resolution. This approach distinguishes the piece from some of her past works like Leaving the institution through cremation is easier than as a result of a deaccession policy, a 2021 letter addressed to the director of the National Museum of Brazil, in which Porras-Kim was concerned with the oldest human fossil, Luzia, after her remains, and most of the collection, were partially incinerated during a disastrous fire at the museum in 2018. Porras-Kim encouraged the museum to finish out the process, burning what was left of Luzia’s remains to allow this body to rest not on display in pieces but in peace. Viewers might anticipate a yes or no decision from the museum. Accompanying this letter is a napkin with the imprint of a hand in ash.

If we are placed in an epistolary purgatory, waiting for a voice that never audibly arrives, these humans are presumed to be in true purgatory, caught between the material world and some afterlife. But if these bodies had been left at the site of the shipwreck, wouldn’t they be just as much stuck in substance? The differences in these possible conditions might simply be of recognition and cohesion. We might not have recognized those scattered, decomposed bits of bone as a body unless they were separated, reassembled, and held together by this institution. What constitutes a body? A corpse? Who constitutes a body? Who reconstitutes a corpse?

A short story by Lydia Davis comes to mind. Titled Grammar Questions, it is a reflection on the difficulty of choosing tenses in discussing the dying and then dead body of her father. “When he is in the form of ashes,” she asks, “will I point to the ashes and say, ‘That is my father’? Or will I say ‘That was my father’? Or ‘Those ashes were my father’? Or ‘Those ashes are what was my father’?” This problem of language at the limits of life returns in her Letter to a Funeral Parlor. Here, like Porras-Kim, Davis chooses the form of an epistolary complaint, objecting to an employee’s use of the word cremains to describe what had become of her father. “Cremains sounds like something invented as a milk substitute in coffee, like Cremora, or Coffee-mate,” she writes. “You could very well continue to employ the term ashes. We are used to it from the Bible, and are even comforted by it. We would not misunderstand. We would know that these ashes are not like the ashes in a fireplace.”

What we call something affects what we do with it, and what we expect others to do with it. As Porras-Kim writes of Luzia in Leaving the institution through cremation, “when you let go of the shape you think she should be as an object, she will return to her life as a corpse once again.” Shapeshifting is an art historical concern of abstraction and illusion, as much as it is a religious and existential one. In all cases, most generative are the instances when we can’t pin something down.